In this series of posts, I’ll be sharing my ideas and experiences of working with multilingual students within monolingual higher education institutions. Like with the previous posts (https://t.co/bBIUxxwt3w), I’m hoping these ideas and experiences will help colleagues in similar learning-teaching contexts to realise the potential of their multilingual students.

The first task described in the series requires students in groups of three to discuss different definitions, understandings, and uses of the terms “leaders” and “managers”. The information they gather should focus on how cultures, beliefs and knowledge systems may have defined these terms, thus they should be encouraged to use any of the languages they know. Once they have critically analysed the information collected, they need to share their analysis with the group in the language used for teaching.

After the different groups have finished their discussion, they may be invited to share the results of their discussions in a plenary session.

Example task: “Leaders” and “Managers”: definitions, understandings, and uses

You’re going to discuss approaches to defining, understanding, and using the terms “leaders” and “managers”. In particular, the discussion will focus on how cultures, beliefs and knowledge systems may have shaped how these terms are defined, understood and used in a particular cultural context.

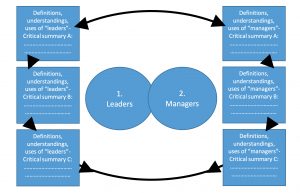

To gather information about these terms, you can read texts written in any of your linguistic repertoires. To discuss the terms, you will present an analytical summary of what you have read in English so that the other two members of your group can contribute to the discussion. Explain whether and how you think culture, beliefs and knowledge systems have helped to shape the information you have read. To complete the task, draw comparisons between the definitions, understandings, and uses of the two terms.

If you wish, you could use the diagram below to organise your comparisons.

Finally, be prepared to share the results of your discussion with the rest of the class. When you share the results, think of how

- you have met the requirements of the task,

- culture, beliefs, knowledge systems may have shaped the concepts investigated, and

- using your linguistic resources has helped you to do the task.